|

Wertham's Ghost

Posted:

February

5, 2002; Revised: April 19, 2006

by The Old Maid

This essay first appeared in World's

Finest Editorials: Pro vs. Con. It is reprinted by permission.

Anyone can say anything. Does that make it true? Anyone can say, for example, that Batman is gay and turns his fans gay. In fact someone did say it. Does saying it make it true?

W hy

does our civilization give to the child not its best but its worst, in

paper, in language, in art, in ideas?

–Fredric Wertham

hy

does our civilization give to the child not its best but its worst, in

paper, in language, in art, in ideas?

–Fredric Wertham

Every comic-book reader has been influenced by Dr. Wertham whether or not they know his name. It was Wertham who wrote Seduction of the Innocent (1954) and testified in the Senate that comic books should be outlawed. The Comic Code seal of approval was the industry’s attempt to placate the government. Wertham remained unimpressed. He insisted that the new comics were as bad as the old, and they still sold age-inappropriate advertisements for patent medicines (body-builder or diet potions, breast-enhancement products) and weapons, including switchblades and guns. Hence his crusade for a legal ban.

Popular history tends to dismiss Dr. Wertham as a quixotic figure who didn’t "get" the comic industry. In fact, he was one of the unsung heroes of the early Civil Rights movement:

"During a distinguished career at some of the nation’s leading hospitals, he fought tirelessly to bring the first psychiatric clinic to Harlem, one that served its patients free of charge. He had become friends with Clarence Darrow when he proved himself one of the few psychiatrists anywhere willing to testify for indigent black defendants, and his research and testimony would play a crucial role in the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case that ended segregation in public schools. For his time, Dr. Wertham was a broad-minded, tolerant, and idealistic advocate for poor and troubled children -– and it was from his idealism that his worst excesses would follow." (American Heritage, July/August 2001, pp. 20-21)

Like Herbert Hoover, Wertham was a man whose successes changed the world. Yet when popular history mentions his name, that one failure is all it remembers.

What the Internet was (and is) without filters and parental supervision, the comics were in Wertham’s day. Lazy parents … lazy parents are the same now as always. Just as parents nowadays assume that animation equals child-friendly, so the parents of yesteryear assumed that comic books meant comic strips (a very different and heavily censored medium) or coloring books. They were wrong. Anyone could print anything, and did:

"It is impossible to deny much of Wertham’s indictment of the medium. Many comics had begun to feature Grand Guignol depictions of severed heads and limbs and graphic shootings and stabbings. The violence was heavily flavored with sex, and nonwhites were depicted as semihuman. Some contained detailed plans for committing crimes" (ibid, p. 20)

Wertham challenged lazy parents to wake up and join his cause. Parents didn’t read comic books. Almost all children read them. Comic books were a new medium, financed primarily by children, and those children were unsupervised. While all of Wertham’s examples were true, the ones he published were chosen for shock value, to force lazy parents to re-examine their assumptions and their actions.

Finally,

Wertham expressed frustration with a child-welfare system he viewed as

outdated and indifferent. "I have gone over many psychiatric charts

of children taken in hospitals, in clinics and by consultants of private

agencies. And I have often been astonished how few quotes, if any, they

contain, of what the children themselves actually say" (Wertham p.

52). He interviewed children. Many times he was the first or only professional

who listened to them. Without a second opinion, though, this meant that

if he ever made a mistake, he would not necessarily know it.

Finally,

Wertham expressed frustration with a child-welfare system he viewed as

outdated and indifferent. "I have gone over many psychiatric charts

of children taken in hospitals, in clinics and by consultants of private

agencies. And I have often been astonished how few quotes, if any, they

contain, of what the children themselves actually say" (Wertham p.

52). He interviewed children. Many times he was the first or only professional

who listened to them. Without a second opinion, though, this meant that

if he ever made a mistake, he would not necessarily know it.

Wertham himself admitted there were good comics, and that comic books alone had not turned an entire generation of children into delinquents. He did believe they tipped the scales. Comic books introduced new ideas; they normalized those ideas; they rationalized those ideas. Wertham believed that parents and governments who let their children read comic books were probably neglecting those children in other ways. Even superhero comics were suspect: Wertham stated that children wouldn’t have been attracted to escapist fantasies if they had a better life at home.

Those readers interested in learning more about Fredric Wertham and the comic industry may wish to read Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, by Amy Kiste Nyberg. Wertham’s book is harder to obtain but worth the effort. Wertham was a brain physiologist; a writer of medical textbooks (his The Brain as an Organ set the standard for its day); a medical anthropologist; a forensic psychiatrist; a social reformer; and an outspoken critic of all media. It is a snapshot of the mind of a relentless and complicated man.

Superhero comics were among the most wholesome entertainment of the genre. Yet Wertham (and the unnamed California doctor from whom he obtained the rest of his research) concluded that the superheroes contributed heavily to the emotional problems of his underage patients. Why? Because the patients said it. That, or Wertham believed they said it, which is not quite the same thing.

Superman,

for example, supposedly promoted violence. Complaints about Superman are

scattered throughout the book, but in total complaints he earned more

ink than any other superhero. (Admit it. You thought Batman held that

distinction.) Superman attacked the same people again and again, while

he himself remained immune to pain or punishment. The more "super"

he was, the better the crowd liked it. The message Wertham got from Superman

is that bullying is fun and socially acceptable. Also, the Kryptonian

was identified and adored as the rightful heir of his superior race, a

term Wertham found chilling.

Superman,

for example, supposedly promoted violence. Complaints about Superman are

scattered throughout the book, but in total complaints he earned more

ink than any other superhero. (Admit it. You thought Batman held that

distinction.) Superman attacked the same people again and again, while

he himself remained immune to pain or punishment. The more "super"

he was, the better the crowd liked it. The message Wertham got from Superman

is that bullying is fun and socially acceptable. Also, the Kryptonian

was identified and adored as the rightful heir of his superior race, a

term Wertham found chilling.

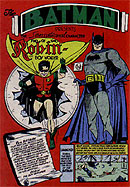

Wertham’s four pages on Batman is his longest single diatribe on any superhero, and anchors the chapter listed as "I want to be a sex maniac!" Batfans may have heard the charges: that Batman turned Robin gay and would turn readers gay. No one was more surprised than the Batman creators themselves. Surely they would know what was going on in Bruce Wayne’s mind, but they didn’t know this. How did Wertham come to this conclusion? He based it on the following items. (All quotes are from Seduction.)

- Bruce Wayne was rich. Several of

Wertham’s patients said they wanted to live with Bruce and be rich

too. "It is like a wish dream of two homosexuals living together"

(p. 190). Here Wertham proposed that Bruce’s money was an aphrodisiac.

- Alfred served lavish meals and kept Wayne Manor filled with freshly cut flowers. This is called stereotyping. So we will address this point immediately and say that a person’s attitude toward flowers or breakfast is not a gender-based or gender-defining characteristic.

- Batman and Robin spent a lot of time caged, trapped or tied up while the other tried to save him. "Like the girls in other stories, Robin is sometimes held captive …. They constantly rescue each other from violent attacks by an unending number of enemies. The feeling is conveyed that we men must stick together because there are so many villainous creatures who have to be exterminated. They lurk not only under every bed but also behind every star in the sky" (p. 190-1). Wertham argued that danger could be stimulating, and that in the wrong circumstances that stimulation could take a sexual turn. He called such stories "erotic rescue fantasies." They were intended, he said, to make Robin more devoted to Batman than to anyone else on earth.

- Bruce and Dick must be homosexual because there were no women in their home. The underlying assumption was that these were sexually active characters and that, lacking appropriate outlets for their passionate urges (i.e. wives) they were compelled to sate those urges with each other. In response let the record show that Robin had been born a boy because the creators didn’t want their moral crusader living alone with an adolescent girl. They were trying to avoid even the appearance of wrongdoing. They had not anticipated this alternate interpretation.

(There was another thing they had not anticipated -- Robin’s name, which has been used in modern times to "prove" the previous point. Shouldn’t a hetero boy have been given a male name? Well, he was. "Robin" is a nickname for Robert, as in Robin Hood. It was not a girl’s name in Wertham’s day. Thank goodness for small favors. I don’t think his heart could have taken it.)

- Bruce and Dick had to be homosexual because the only women in their lives were criminals like Catwoman. Very different from the above. Here Batman stood accused of two counts of misogyny. On one count, it was implied that the horrible women in Batman’s life would turn anybody gay. On the other count, it was implied that if a good woman ever did visit Batman’s world she wouldn’t live very long. Yes, it is true that Batman rarely associated with any person, male or female, who had no connection to a crime (and therefore no connection to the plot). It should be noted, though, that Wertham had not invented this complaint the day he read his first Batman book. It was a pre-existing plank in his reformist campaign. Wertham loathed all media for their portrayals of women. Crime stories ranked among the worst offenders. If good women became victims, empowered women became criminals, and all women characters were reckless or stupid, then to Wertham’s mind the solution was to stop putting them in crime stories. This in turn could kill the crime story genre – which was exactly what he wanted.

- Bruce Wayne wore pajamas and dressing gown around his house; he sat on the same sofa or couch as his youthful ward; Dick often sat at Bruce’s bedside when his guardian was injured or ill. This point is hard to address because family norms are influenced by ethnic and/or cultural bias. They’re also a product of their time. It’s easy for a Batfan to ask why Bruce cannot wear pajamas in the privacy of his own home, but that’s an ethnocentric attitude. Even in the 21st Century many families insist that their members be fully dressed before they mingle or meet at the breakfast table. There were even more such families in Wertham’s day. In any event Wertham considered Bruce’s behavior immodest and inappropriate because the little boy was a guest in Bruce’s home, not a blood relative. See the next point.

- Robin had no pants on. This does not prove Batman and Robin are gay. Proves they’re idiots, though. Wertham’s patients commented that Robin looked like a girl. Why? Because he had no pants on. The problem was not that Robin dressed like a girl (he certainly did not; girls wore more clothes than he wore), but that he was undressed like a girl. That is, Robin presumably began with all his clothes then systematically lost them. By definition a sexual object must lose her clothing as the story progresses; it illustrates her degradation. The fact that the civilian character, Dick Grayson, knew perfectly well what constituted polite dress only made the characters look more guilty. Robin trespassed on the comic-book formula that only victims/sexual objects had no pants on.

Let’s look at one case study in particular (p. 192), proof that there’s no substitute for going back to the source:

"One young homosexual during psychotherapy brought us a copy of Detective Comics, with a Batman story. He pointed out a picture of ‘The Home of Bruce and Dick,’ a house beautifully landscaped, warmly lighted and showing the devoted pair side by side, looking out a picture window. When he was eight this boy had realized from fantasies about comic-book pictures that he was aroused by men. At the age of ten or eleven, ‘I found my liking, my sexual desires, in comic books. I think I put myself in the position of Robin. I did want to have relations with Batman. The only suggestion of homosexuality may be that they seem to be so close to each other. I remember the first time I came across the page mentioning the Secret Bat Cave. The thought of Batman and Robin living together and possibly having sex relations came to my mind. You can almost connect yourself with the people. I was put in the position of the rescued rather than the rescuer. I felt I’d like to be loved by someone like Batman or Superman.’"

E xcuse

me? Batman or Superman? We know the speaker did not propose that Superman

turned him gay. But if Batman and Robin had never existed, could the speaker

have had the same feelings and problems? It’s possible this interview

included "leading" questions and answers of which we are unaware.

The speaker may have been struggling with his sexual orientation, but

it does not follow that the superheroes have changed theirs.

xcuse

me? Batman or Superman? We know the speaker did not propose that Superman

turned him gay. But if Batman and Robin had never existed, could the speaker

have had the same feelings and problems? It’s possible this interview

included "leading" questions and answers of which we are unaware.

The speaker may have been struggling with his sexual orientation, but

it does not follow that the superheroes have changed theirs.

Loneliness, fear, and a desire to feel safe and loved are not gender-based or gender-defining characteristics. The problem is the introduction of sexual attraction into the caregiver-and-child context. Any such contact, under any circumstances, is unacceptable. This is why Wertham argued that Batman had turned Robin gay instead of, say, choosing a lover of consenting age who was already homosexual (though Wertham wouldn’t have liked that either). He proposed that the Bat selected an impoverished youth, enticed him with wealth and adventures, and then seduced him with sensual behavior. Batman had taught him that it was normal for caregivers to behave in a seductive manner. Only after Robin internalized this lesson would Robin reciprocate. Therefore if Robin could be taught, so could the audience.

In one sense Wertham was correct: the comics may have helped patients find words for their troubles. He then argued that comic books caused such troubles. However, this meant Wertham had to convince people that if comic books did not exist, more of his patients could have grown up heterosexual.

Wertham’s case against non-superhero comics was surprisingly strong, but his case against Batman was weak. (The opposite of public perception.) Even so, the charges stuck. How could the Bat mythos respond to this attack? Well, it could take the direct approach. (More on this later.) Instead it took the indirect approach – and dug such a deep hole for itself that Bats still struggles to climb out to this day.