|

Story Analysis: "Day of the Samurai"

Posted:

May 22, 2006

Batman: The Animated Series comprises a series of independent stories featuring clever premises, colorful characters, strong conflicts, smart dialogue, and bold visuals. Alone or in combination, these elements are enough to make the series a stylish success. These are also the elements that most fanfictions strive to emulate.

Batman: The Animated Series comprises a series of independent stories featuring clever premises, colorful characters, strong conflicts, smart dialogue, and bold visuals. Alone or in combination, these elements are enough to make the series a stylish success. These are also the elements that most fanfictions strive to emulate.

But the stories work as integrated wholes not because they have the above features, but because they knit them together into strongly constructed stories. An analogy: a skyscraper is more than a series of boxes stacked atop each other and wrapped in an attractive skin of stone and glass. It has a invisible inner construction that that makes it strong and stable. The best BTAS stories have a similar internal structure and unity.

The following essay is not a review but a story analysis of "Day of the Samurai." That is not the best BTAS story the series ever gave us. In fact, it has significant flaws. But it is an ambitious and interesting story, and by examining its flaws you can actually gain a greater appreciation of what it does right and a better understanding of why other episodes work better. That, at any rate, is the indirect purpose of this analysis: to lay bare the skillful construction that goes into its story, and to see how a professionally written story can transcend the elements that it shares with its fanfic imitators.

Day of the Samurai (Story editor: Michael Reaves) Written by Steve Perry • Directed by Bruce W. Timm • Storyboards by Michael Diederich, Mike Goguen, Gary Graham, Brad Rader, Bruce W. Timm, and Mark Wallace

I. Scene Structure

Let's start our analysis by breaking the story down into its individual scenes. The table below numbers each scene, describes its essential action, and gives its running time and location on the DVD (Batman: The Animated Series, Volume 2, Disc 3, Track 2).

| Scene | Action | Location | Running Time |

| 1 | Kyodai Ken (the Ninja) attacks/kidnaps Kairi. |

|

|

| 2 | Yoru Sensei finds the ransom note. |

|

|

| 3 | Batman learns of the kidnapping. | 3:05 |

0:20 |

| 4 | Kyodai Ken reveals that Kairi is only an element in a larger plot. | 3:25 |

|

| 5 | Wayne reveals his sense of obligation to Yoru Sensei. | 3:45 |

|

| 6 | Yoru Sensei implies that he knows Bruce Wayne is Batman | 4:30 |

|

| 7a | Bruce Wayne reveals that Kyodai Ken knows that he is Batman. | 5:00 |

|

| 7b* | Once upon a time, a warrior invented a powerful fighting technique. | 5:50 |

|

| 7c | Bruce Wayne reveals that Kyodai Ken will exchange Kairi for a map showing the hiding place of the scroll containing the secret fighting technique. |

|

|

| 8 | Bushido forces Yoru Sensei and Wayne to yield to the Ninja's demands. | 7:45 |

|

| 9 | Batman sacrifices the map to save Kairi after the Ninja tries to kill her. | 8:25 |

|

| 10 | The Ninja escapes from Batman. | 9:40 |

|

| 11 | Kyodai Ken retrieves the scroll. It disintegrates, but he saves a piece. | 11:00 |

|

| 12 | Batman retrieves the remnants of the scroll. He and Yoru Sensei suspect the Ninja has a piece containing the secret of the technique's deadly "touch." | 12:05 |

|

| 13 | The local volcano is becoming more active. | 12:35 |

|

| 14 | Batman confirms to Alfred that the Ninja has the most important part of the scroll. He declines to leave for America. | 12:55 |

|

| 15 | Kyodai Ken deciphers the scroll and shows that he has mastered the deadly "touch." | 13:30 |

|

| 16 | Bruce Wayne and Yoru Sensei realize that they don't know enough to protect Batman from the "Eternal Sleep" touch. | 14:10 |

|

| 17 | Alfred and Kyodai Ken shop in the same street market. | 14:30 |

|

| 18 | Kyodai Ken holds Alfred hostage and blackmails Wayne into meeting him. Wayne traces the call. | 14:50 |

|

| 19 | Kyodai Ken gloats over Alfred and demonstrates his knowledge of the touch on a practice dummy. | 15:25 |

|

| 20 | Wayne tells Kairi that Batman will meet the Ninja. | 16:00 |

|

| 21 | Batman explores the Ninja's lair and studies his practice dummy. | 16:00 |

|

| 22 | Batman and the Ninja meet on the volcano; they decide to fight without masks. | 16:20 |

|

| 23 | Batman and the Ninja fight inconclusively. | 17:15 |

|

| 24 | The volcano erupts; the Ninja insists on continuing the fight. | 17:40 |

|

| 25 | The Ninja presses his attack and uses the touch. Batman collapses. | 18:00 |

|

| 26 | Batman revives and attacks the Ninja. When they are separated by a lava flow, Batman tries to save Kyodai Ken, but the Ninja commits seppuku instead. | 18:45 |

|

| 27 | Batman tells how Alfred how he defeated the "Eternal Sleep" touch. | 20:20 |

|

| 28 | Yoru Sensei praises Batman (through Bruce Wayne) for having the essence of samurai. | 20:50 |

|

* Scene 7b is a flashback folded inside Scene 7 and narrated by Bruce Wayne from within that scene.

II. Theme

My description of Scene 28 sounds stark, but that is its explicit content:

My description of Scene 28 sounds stark, but that is its explicit content:

YORU SENSEI

If you see Batman, tell him I have great respect for him.BRUCE WAYNE

Why? He's as much a ninja as Kyodai was.YORU SENSEI

Not so. Batman offered to help his adversary. And a lesser man would have used the knowledge of the [omemri] touch against his opponent. Batman is the essence of samurai, Wayne-san. You would do well to remember that.

This denouement explicitly states the theme of the episode: Batman's actions are dictated and controlled by a strong and praiseworthy moral code. But the episode does not merely give us this theme as a pat little moral at the end. The entire story is designed to illustrate it.

If we look back at the above structure, we can see earlier scenes that plant and develop the idea:

Scene 5: Wayne reveals his sense of obligation to Yoru Sensei.

Scene 8: Bushido forces Yoru Sensei and Wayne to yield to the Ninja's demands.

Scene 9: Batman sacrifices the map to save Kairi after the Ninja tries to kill her.

Scene 14: Bruce Wayne declines to leave for America.

Scene 20: Wayne tells Kairi that Batman will meet the Ninja.

Both implicitly and explicitly the story contrasts Batman/Bruce Wayne with the Ninja/Kyodai Ken. The Ninja will play any dirty trick, including kidnapping, blackmail, and attempted murder, to get what he wants. Batman will not. The clearest moment comes in Scene 9, where Kyodai Ken seeks an advantage by kicking Kairi off a skyscraper so as to distract Batman from the map. To save Kairi, Batman sacrifices the chance to protect himself by keeping hold of the map.

The conflict illustrated by the running battle between Batman and the Ninja might be described as one between "core moral values" and expedience. Kyodai Ken will do anything to anyone if it gets him a temporary advantage. Batman is constantly tempted to do the same, but he never yields, preferring to stay true to his samurai-like code.

At the end of the story, two lessons have been offered. First, we learn that Batman can triumph despite his scruples because he augments those scruples with superior skills and smarts. Second, we learn that the Ninja's preference for expedience has wedged him in a logical cleft: At the end, he can either sacrifice his life by rejecting the lifeline Batman throws to him, or he can sacrifice his self-respect by accepting it. This is where his preference for expedience has led him: whatever he does, he will suffer a kind of extinction.

We'll return to this last idea later. For now, though, let's note how it connects with a recurrent motif about identity: Kyodai Ken knows that Bruce Wayne is Batman. The plot of the story doesn't require that he possess this knowledge: he would be just as deadly a threat even if he never made that connection. But because he knows who Batman is, Kyodai Ken stands as not just a physical threat to Bruce Wayne (will he kill our hero?), and not just a moral threat (will he cause our hero to betray his own principles?), but as an existential threat. If Kyodai Ken survives this episode, then Batman/Bruce Wayne may not be safe in either of his two guises. He might be forced to give up both identities.

Note further the contrast with Yoru Sensei. It is all but stated that Bruce's old mentor knows that he is Batman. But Yoru Sensei is not a threat, because his own code of honor would never let him use that knowledge against his ex-pupil, and he signals his reluctance to use it by refusing to explicitly announce that he knows they are the same man.

In this way the story shows that physical, moral, and existential safety are intertwined, So too are physical, moral, and existential identity. By maintaining his moral integrity, Batman preserves the other two. Kyodai Ken, by sacrificing his integrity for short-term advantage, winds up losing his life (and, as we shall see, even his identity) at the end.

III. Structure

With what we have just said in mind, we can now examine the general structure of the story and see how it develops and illustrates this theme. We can also see how it builds tension and suspense in the narrative.

With what we have just said in mind, we can now examine the general structure of the story and see how it develops and illustrates this theme. We can also see how it builds tension and suspense in the narrative.

As the story begins, Batman is not directly implicated in the plot. True, if you have seen "Night of the Ninja" then you know that Kyodai Ken holds a grudge against Bruce Wayne. But his kidnapping of Kairi is not obviously a stroke against Wayne, and our hero has no immediate grounds to suspect he is the object of the Ninja's plot. Instead, he enters the story as someone who can help Kairi and Yoru Sensei. At this point in the narrative (Scene 5), the story illustrates Batman's code of honor by showing his sense of obligation to his old mentor. Already he is being called upon to defend his moral code, but it takes the form of his being forced to defend his friends.

The first climax comes at the end of Scene 7, when Wayne reveals to Alfred that the Ninja knows who Batman is. This increases the tension by exacerbating the conflict. It is no longer enough that Batman protect his friends; now he himself is in danger.

The second act begins with Scene 8, which is another theme-development scene. Wayne is tempted by circumstances to "cheat"ˇafter all, he too is now in the crosshairs. Moreover, this scene, in conjunction with Scene 7, puts moral pressure on Wayne: He must defend himself not just by surviving physically but by declining to betray his morals. He demonstrates his willingness to do this in the next scene, when he sacrifices the map in order to save Kairi. (Of course, he's not a sucker, and tries his best to save both.) Note also that this scene resolves the conflict set up in the first actˇwith Kairi's rescue, she and Yoru Sensei are no longer in danger. By doing this, the story is free to concentrate on developing and resolving Wayne's problems.

The rest of the act increases the tension by giving Kyodai Ken the key scrap of paper that will let him defeat Batman while also rubbing Batman's face in the fact that he will not be able to use the same knowledge to defend himself. The Ninja has part of the scroll; Batman has the rest of it; and this "close but no cigar" result forcefully emphasizes that Batman will be on his own in the climactic fight. He is not only defending himself; he can rely on nothing but himself and his own skills in order to survive.

The act ends when one last chance to escape presents itself: Alfred points out that, with the rescue of Kairi, there is no reason Wayne must stay in Japan. True, the Ninja will likely follow him to Gotham even if he leaves. But by choosing to stay, Wayne announces his commitment to resolve the conflict immediately, even if it is on grounds of his enemy's choosing. This scene is another statement of the story's theme. The act is bookended by these statements, and by structurally progressing from a "temptation" scene to a "decision" scene, the act illustrates Wayne's commitment to defend his integrity.

The third act has Batman facing off directly against Kyodai Ken, undistracted by other problems. It also shows him turning things around by using his own wits to defeat the Ninja. Until this act he has been mostly reactive, responding to the Ninja's actions and provocations. Now Batman takes his own measures, showing that someone with his scruples is not hampered by them but is free to augment them with ingenuity and elementary cunning. That is the purposeˇeven more than as just a plot elementˇof Wayne's tracking Kyodai Ken's blackmailing call (in Scene 18) and his examination of the Ninja's practice dummy in Scene 21.

The climactic moment of both the third act and the story as a whole occurs in Scene 26, when he and the Ninja are separated by a lava flow. He is given a final choice: he can let the Ninja go to his doom, or he can try to save his enemy. He chooses the latter. This, of course, is pretty much a no-brainer for him, for the ethical code he has been protecting throughout the story requires him to act in this noble way. Still, it is the most important moment, for it is the moment when his morals are put under the greatest stress. It would be easyˇexpedientˇfor him to let the Ninja go under with the excuse that there was nothing he could do to save him. It would also make his identity as Batman/Bruce Wayne safe. But the appalling costˇhe would sacrifice his moral integrity if he were to do thisˇdeters him from taking the easy way out. At this moment, he recommits himself to his code.

IV. Climax

It's worth looking at this climactic moment in more detail, because the climactic moment of a story is its real endpoint. And the ending of a story is when that story comes into sharpest focus. It's also worth examining because there is an undeniable feeling of unearned resolutionˇof deus ex machinaˇin this scene.

It's worth looking at this climactic moment in more detail, because the climactic moment of a story is its real endpoint. And the ending of a story is when that story comes into sharpest focus. It's also worth examining because there is an undeniable feeling of unearned resolutionˇof deus ex machinaˇin this scene.

We've already sketched what this climactic moment means for Bruce Wayne: He must choose between guaranteeing his personal survival and protecting his moral integrity. He chooses the latter.

We have also sketched what it means for Kyodai Ken, who faces a similar dilemma: He must choose between his physical safety and his sense of self-respect.

By lining these choices up, so that self-respect for the Ninja is the equivalent of moral integrity for Batman, the episode shows that self-respect and fidelity to core morals are closely related. Moreover, it shows that moral honor and self-respect play equivalent roles in the antagonists' psychologies. And, interestingly, Kyodai Ken makes the same choice as Wayne: he is willing to gambleˇin his case with a sure knowledge that he will loseˇhis physical survival to save his self-respect.

This is a significant irony, for Kyodai Ken has throughout the story stood for expedience in the service of self-interest. The ending, and the nature of the choice confronting the Ninja, show that a preference for expedience leads ultimately to self-betrayal: whether he commits seppuku or grasps the Bat-line, the Ninja will betray something he values immensely—either his own skin or his own ego. Whatever he chooses, his devotion to advantage and self-interest has led him, necessarily, to extinction.

When put in this no-win situation, however, he finally gives up his habit of reaching for the expedient; in choosing physical annihilation, Kyodai Ken is abandoning his implicit moral code (which has proven treacherous even to himself) and embracing an even greater nullity: his pride and ego. The Ninja's character is defined (both here and in "Night of the Ninja") almost entirely in negations: he is what Batman/Bruce Wayne is not. With his final choice he embraces the ultimate negation: death.

More irony: By choosing to protect his ego and sense of self-respect he is acting to protect his character, the unity of attributes, habits, preferences, dispositions, and actions that make him who he is. In this way he realigns toward Bruce Wayne's own choice, which is to remain faithful to the code that has, over the decades, inscribed his own character. In other words, by the end Wayne hasn't changed, but Kyodai Ken has. This changeˇthis evolution toward what Batman stands for, even though it can only end in deathˇis foreshadowed in Scene 22 when Kyodai Ken deliberately abandons his ninja maskˇand, implicitly, what it stands forˇso that he can fight with naked face: in other words, with his own character bared.

This is a subtle, powerful, and provocative climax. By ending this way, the episode has illustrated Batman's resilient attachment to principle, and it has also led Kyodai Ken to a tragic, unexpected, but (in retrospect) inevitable end. And yet it feels like a cheat. Why?

The fact is that thematic strength does not equal narrative strength, and the story contains a subtle but crippling flaw.

The nature of drama is simple enough to state: A classical drama is a narrative about a character who makes an irreversible choice that alters his being in some vital way. The narrative, in turn, is organized so that the tension and suspense of the story is continually increased until it reaches a point where the character, having evaded or worked through obstacles, makes that fundamental choice. The moment of choice is the story's climax.

When we look back at the events of "Day of the Samurai," we see that Kyodai Ken is the one who changes, and the climactic moment is thematically structured to show why he must change, even though it is a change that will lead to his death. But when we elaborated the story's structure we charted a tension that applied to Bruce Wayne.

In short, then, we have a narrative structure and a thematic climax that do not fit together. The narrative structure implies a climax at which Batman will not only make a choice but undergo a change. But though he more clearly understands himself at the end of the storyˇthanks, at least in part, to Yoru Sensei's little speechˇBruce Wayne has not undergone a fundamental change. In fact, he has successfully resisted every temptation to change. "Day of the Samurai" puts the screws to Batman, but it only succeeds in showing how hard it is to break him. Instead, the fundamental changeˇdescribed aboveˇis in his adversary, Kyodai Ken. He is the character who changes, but the narrative arc is not arranged as a series of tests directed at him.

Because the narrative and the climax don't connect with each other, the latter feels arbitrary relative to the former. This is a deeper problem than you might suspect at first. On the surface, the final scene seems arbitrary, because it seems coincidental that the final fight should take place on an erupting volcano, and that Kyodai Ken, rather than Bruce Wayne, should get trapped by a lava flow. In fact, a clever story could have kept this exact ending but better motivated it by organizing its narrative around the Ninja and by showing how he betrayed himself into that impossible position. The best example of how to do this is in "Mad as a Hatter," whose villain, Jervis Tetch, also prefers solving his problems by taking the easy way out, and who also destroys what he loves most because he has made a series of foolish choices. "Day of the Samurai," if it had built its plot arc around the Ninja, could have taken Kyodai Ken along a similar journey.

This disconnect between the narrative and the climax is a fundamental flaw in the story. You can see the problem coming from a long ways off. The story is organized around Batman, and he can't change. (That, by the way, is one reason so many of the best BTAS stories revolve around the villains, with Batman himself as little more than a supporting character.) Though the story is tense and suspenseful until the very end, that tension can only be discharged in an unsatisfactory way by breaking the antagonist, rather than the protagonist. Moreover, even though the climax presents Wayne with a choice, it's a choice whose obvious consequences won't be able to relax the tension. If Batman saves the Ninja, then his survival and his identity will remain in jeopardy. If he deliberately lets the Ninja die, then he will have undergone a change, but it will be one that represents a defeat and diminishes his character. In short: Given the logic of the situation, Kyodai Ken must die. But Batman can't kill him. Thus, only a deus ex machina can resolve this dilemma: literally, the author intervenes by providing a convenient volcanic eruption in order to get his main character out of an impossible situation.

V. Narrative Weaknesses

The flaw described above is fundamental; in truth, it could only be fixed by keeping the present ending, junking everything that comes before, and starting over with a new narrative that takes Kyodai Ken as protagonist and concentrates on charting his, not Wayne's, evolution. But even as the story stands now there are other weaknesses.

The flaw described above is fundamental; in truth, it could only be fixed by keeping the present ending, junking everything that comes before, and starting over with a new narrative that takes Kyodai Ken as protagonist and concentrates on charting his, not Wayne's, evolution. But even as the story stands now there are other weaknesses.

"Day of the Samurai," despite its suspense, has a very leisurely pace. Its basic story is very taut, but it takes its time working through it. That is because it inefficiently rolls out its exposition in unnecessary scenes.

Consider Scenes 2, 3, 4, and 6 and what they accomplish:

Scene 2: Yoru Sensei finds the ransom note.The information these scenes impart is important, but much of it could be implied without being shown. Scene 2, for instance, could almost certainly be cut. Partly this is due to genre conventions: it's a given that someone would find Kyodai Ken's ransom note. (Only in a farcical parody of a noir thriller would a ransom note go undiscovered.) But the story already has elements to handle the content of this scene. Scene 1 has planted the existence of a ransom note; Scene 3 explicitly alludes to Yoru Sensei. Because Scene 2 contains only those two elements, and because his finding the ransom note can be inferred from actions shown later in the story, Scene 2 is itself superfluous. Similar remarks could be made about Scenes 3 and 4. Even the info given in Scene 5 (necessary thematic material) could probably have been folded into Scene 6, and with ingenuity both it and the content of Scene 6 might have been folded into Scene 7, which is the longest and most necessary expository scene.

Scene 3: Batman learns of the kidnapping.

Scene 4: Kyodai Ken reveals that Kairi is only an element in a larger plot.

Scene 6: Yoru Sensei implies that he knows Bruce Wayne is Batman.

Instead, we are given one minute and thirty seconds of dead, unnecessary scenes to slog through before getting to the good stuff in Scene 7.

The episode is also quite leisurely about setting up the scroll and who can glean what knowledge from it. Scenes 12, 15, 16, and 19 collectively tell us that Kyodai Ken has the necessary part of the text, that he has extracted the necessary knowledge from it, and that Batman can't defend himself by using what is left. Really, only two scenes are needed to get this stuff across. Scene 19 helps set up Scene 21, but what we learn in Scenes 15 and 16 probably could have been more efficiently imparted in Scenes 12 and 19. Approximately another minute of screen time could have been shaved.

Scene 13 is deadwood. It sets up the later eruption, but that could have been effectively established at the end of Scene 12, where an eruption, if done in the background and noticed by the characters, could have evocatively set off Yoru Sensei's line "I think the Batman is in grave danger" while serving as a metaphor for the increasing tensions. Doing things that way could also have saved, perhaps, 15 seconds of screen time.

Scene 20 tells us little that we haven't learned in Scene 14, except that Kairi shows some gratitude and concern. By itself, this isn't enough to justify the redundancy. That's another twenty-five seconds that could have been cut.

Scene 10 is the most egregiously unnecessary scene. It merely continues the fight that had been concluded in Scene 9 by bringing Batman and the Ninja together for no good reason and no necessary effect. That's one minute and twenty seconds that don't advance the story.

Add it all up, and there's about four and a half minutes of scenes that slow the story down. That's nearly one-quarter of the total running time, which isn't far short of the length of a full act. True, it's not obvious how that time could have been better spent, but it's time ill-used nonetheless.

VI. Dialogue and Direction

These expository scenes are mostly unnecessary; that doesn't mean they are unskillful. It is sometimes said that a good film would be intelligible even if it were dubbed into an unfamiliar language, which is an evocative way of saying that the images, not the talk, should carry the story. BTAS is often very good at this, and "Day of the Samurai" is no exception.

Consider the following dialogue transcriptions from Scenes 2, 3, 15, and 19 and how the dialogue does not itself impart the expository material

In three of these examples, my description is even longer than the dialogue the scene contains. That's because the essential information is either given visually or implied by the actions we are shown.Scene 2: Yoru Sensei finds the ransom note.

YORU SENSEI

Gasp!Scene 3: Batman learns of the kidnapping.

ALFRED

Master Bruce!BATMAN

What is it, Alfred?ALFRED

Yoru Sensei, line three.BATMAN

Konichiwa, Sensei.Scene 15: Kyodai Ken deciphers the scroll and shows that he has mastered the deadly "touch."

KYODAI KEN

Ah, who would guess it was there?Scene 19: Kyodai Ken gloats over Alfred and demonstrates his knowledge of the touch on a practice dummy.

KYODAI KEN

A single touch. That's all it will take to destroy your master!

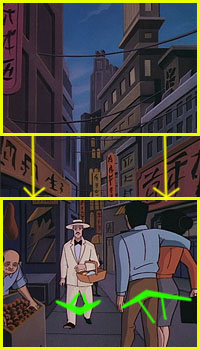

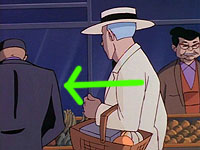

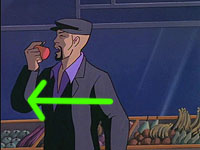

Scene 17 (amateurishly storyboarded below with screengrabs) is an especially good example of subtle direction:

|

|

|

|

|

|

This moment creates suspense. We know before this scene starts that Batman and the Ninja must meet. How will that meeting be pulled off? This scene, by simply showing Alfred and the Ninja in close proximity, tells us that Alfred will be the connection. But because he and Kyodai Ken are shown going about some apparently innocent business, we are not sure how the connection will be pulled off. Will the Ninja kidnap Alfred? Or will Alfred recognize and follow the Ninja? The moment is not really ambiguous, because the very next scene shows that Kyodai Ken has captured Alfred, but the oblique staging creates anticipation and suspense; when paired with the scene that follows it also tells us that a kidnapping has occurred while sparing us the tedious details of how the Ninja managed to grab Alfred and maneuver him back to his hideout.

"Day of the Samurai" is full of these surefooted touches, which is one reason that, despite its heavy expository load, it never drags. Other examples of oblique, visual storytelling are left as an exercise for the reader to discover.

I opened this essay by negatively comparing "Day of the Samurai" to fanfics, but professionals too often also write flat stories. And even when they're good at story construction, they can degenerate into formula.

But skillful writing is not a function of scope or length; even a good joke, if well-told, should build to an explosive climax. BTAS was so successful, at least in part, because its producers understood this. They didn't always succeed, and occasionally they didn't even seem to try. But most of the episodes they created can stand, in their miniature way, next to much longer films and repay close attention.